Some of you may recall the doctor who helped the Ingalls family when they fell ill in Chapter 15, “Fever ‘N’ Ague” of Little House on the Prairie. He was based on George A. Tann, a pioneer, physician, and neighbor of the Ingalls family. We are excited to explore the real-life of Dr. George A. Tann.

Late summer in the Midwest is hot, humid, and buggy! In Chapter 15, “Fever ‘N’ Ague” of Little House on the Prairie, the heat is so intense that Laura and Ma have to stop picking blackberries in the creek bottoms and sit in the shade. They aren’t the only ones interested in the berries; mosquitoes swarm and buzz in the briers, biting and speckling Laura across her forehead.

Ma picks blackberries in Chapter 15 of Little House on the Prairie. Illustration by Garth Williams.

Within the next few days, the entire Ingalls family is afflicted with aches, chills, and fevers. Unbeknownst to them, it’s malaria. As Laura drifts in and out of consciousness, she can vaguely hear Jack the Bulldog howling and strange voices urging her to drink.

A feverish Laura crawls across the floor taking a dipper of water to her bedridden sister Mary while faithful Jack the brindle bulldog remains by her side in Chapter 15 of Little House on the Prairie. Illustration by Garth Williams.

When Laura opens her eyes, she sees a black doctor and a neighbor woman medically ministering to her family. Dr. Tan, the doctor to the Osage and area settlers has arrived, apparently upon the insistence of Jack, who stops him on his way north to Independence, Kansas.

Dr. Tan and Mrs. Scott tend to the Ingalls family in Chapter 15 of Little House on the Prairie. Illustration by Garth Williams.

After a short stay, Dr. Tan continues on his way caring for the ill pioneer families who live along the creek. As the chapter closes, Laura tells us that Pa makes a rocking chair for Ma out of willow saplings, so she can rest comfortably while recovering.

The rocking chair Pa makes for Ma from slender willows in Chapter 15 of Little House on the Prairie. Illustration by Garth Williams.

What Laura doesn’t relate, and perhaps did not know at the time, was that Dr. Tan (spelled Tann, according to historical records) was a neighbor of the Ingalls, living less than one mile north of their property. Laura also recorded in her nonfiction memoir, Pioneer Girl, edited by Pamela Smith Hill, that Dr. Tann delivered her sister Carrie on August 3, 1870. According to researcher Eileen Charbo, the doctor was known for delivering babies for the “best families” in Montgomery County, Kansas, and was well-known for his reasonable rates.

George A. Tann was born into a free black family on November 27, 1835, according to the census report and land records (though his gravestone indicates he was born ten years earlier in 1825). Working alongside his father Bennet on their Pennsylvania farm did not leave much time for school. George was probably educated in a home or rented storefront, as were many black children in the area. After leaving the farm, George made a living as a peddler while supporting his wife, mother-in-law, and infant son. He sold herbal remedies during his career as a peddler and may have become familiar with homeopathic medicines.

Dr. Tann became known as a doctor of “eclectic” medicine. A popular and widely-practiced medicine of the day, eclectic medicine combined botanical remedies with physical therapy to achieve health and wellness. There are no documents that show George Tann’s enrollment in medical school. Most blacks learned by apprenticeship or were self-taught. Dr. Tann learned his profession well, becoming particularly skilled in setting bones. Taking advantage of the Homestead Act and free Kansas land, he and his father relocated and purchased property neighboring Charles P. Ingalls.

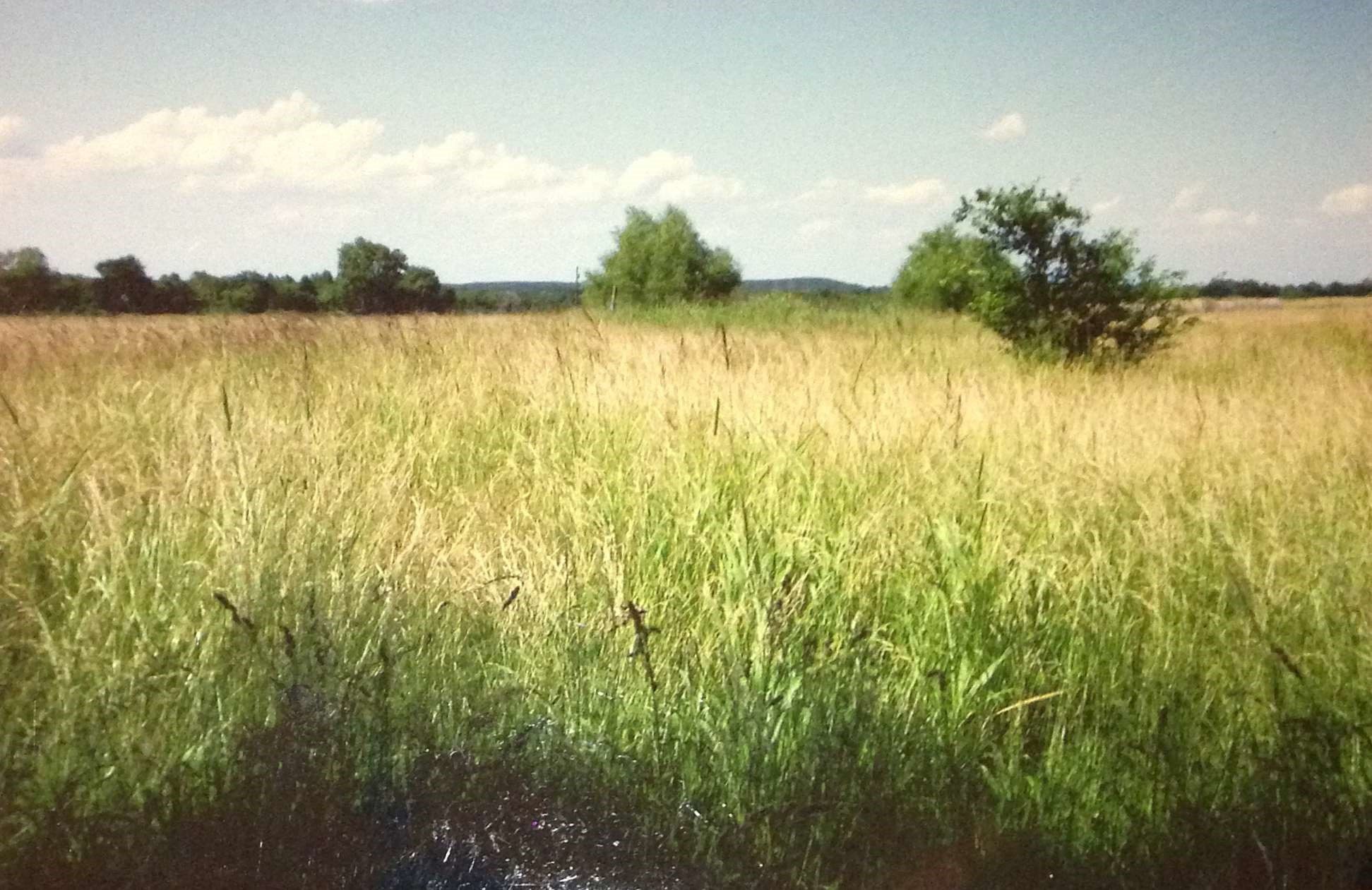

Dr. Tann’s property (present day). Photo courtesy of Susan Thurlow.

In the final chapter of Little House on the Prairie, we find the Ingalls family leaving the “Indian Territory” (the Osage Diminished Reserve). Dr. Tann, however, remained in Kansas. In addition to establishing thriving medical practices in Independence, Kansas, and Oklahoma Cherokee Nation, Dr. Tann acquired hundreds of acres of land with fruit trees, a hen house, hog pen, and stable. Laborers, farmers, and housekeepers worked his properties. According to researcher Nansie Cleveland, Dr. Tann also homesteaded in South Dakota for a time.

A watercolor rendition of Dr. Tann’s office and adjacent blacksmith shop painted by Grace Thurlow based on a 1937 newspaper article from Bartlesville, Oklahoma, which included the description of his office in 1891. Courtesy of Susan Thurlow.

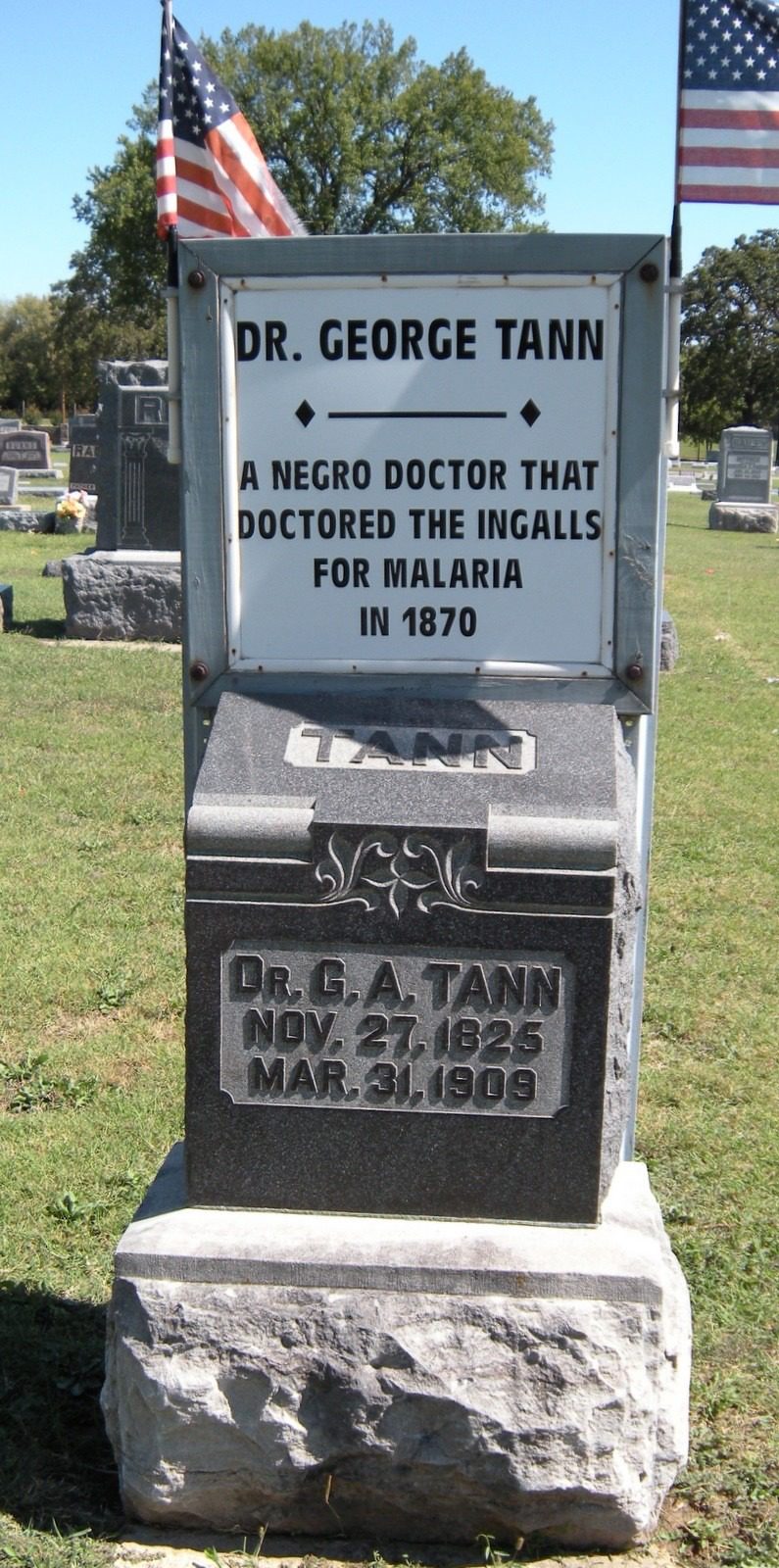

Dr. Tann retired in 1902 at age 67 and died in 1909, after suffering a heart attack following a horse and buggy accident. Kansas State Historical Society documents record that the people of Independence held Dr. Tann in such high regard that he was not buried in the traditionally separate black section of the cemetery, but was laid to rest in a prominent spot in gratitude for his selfless service to the community. His gravesite can be seen today in the Mt. Hope Cemetery in Independence.

George A. Tann’s gravesite in the Mt. Hope Cemetery in Independence, Kansas. It is believed he was actually born in 1835.

A watercolor rendition of Dr. Tann’s gravesite painted by Grace Thurlow. Courtesy of Susan Thurlow.

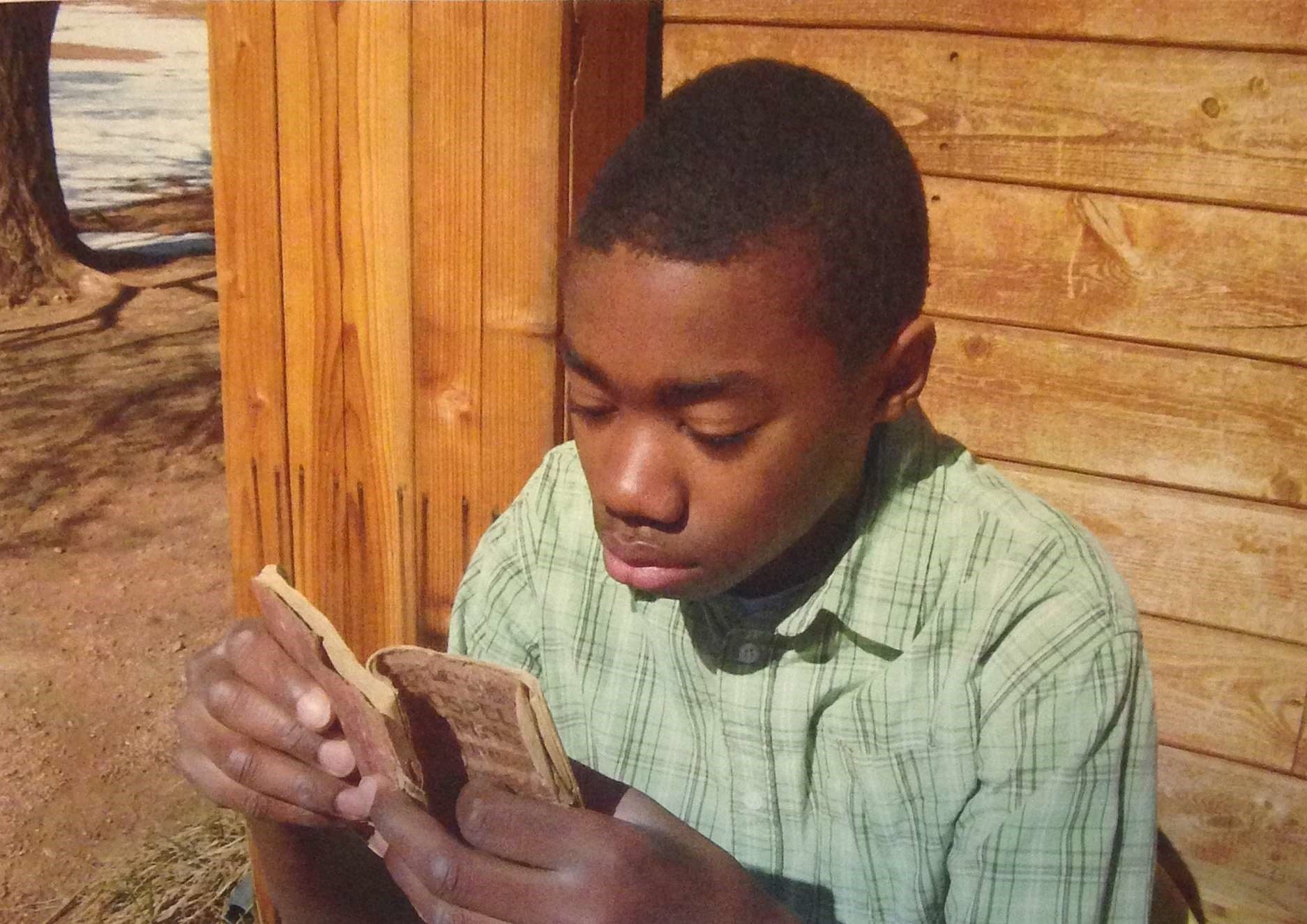

I first began the task of bringing Dr. Tann’s remarkable story to life for a 2012 presentation for the Laura Ingalls Wilder Legacy and Research Association. It quickly turned into a fun and educational project for our four children. I wanted to help them connect with the Little House books that I had loved as a child. Our daughters, Esther and Annie, modeled Dr. Tann’s daughters for the visual portion of the presentation while our son, Franklin, portrayed a young George Tann. Our oldest daughter, Grace, painted watercolors from historically-researched and period photographs. Without my husband Mark’s encouragement, the project would not have been completed.

Anna Thurlow as Dr. Tann's daughter Stella Tann. Photo courtesy of Susan Thurlow.

Esther Thurlow as Dr. Tann's daughter Naomi Tann. Photo courtesy of Susan Thurlow.

Franklin Thurlow reading a gospel hymn book that a quiet and studious George Tann might have studied. Photo courtesy of Susan Thurlow.

This has been a fantastic journey into black frontier history for all of us. I was privileged to correspond with Eileen Charbo, author of A Doctor Fetched by the Family Dog: The Story of Dr. George A. Tann, Pioneer Black Physician, before her passing. Mary R. Guinter, Cemetery Chairman LCGW, Lycoming County, Pennsylvania, was instrumental in helping me piece together Dr. Tann’s early life. Documents and resources from the Kansas State Historical Society, the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, and the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum were all useful in adding another piece to the Dr. Tann story begun by Laura Ingalls Wilder in Little House on the Prairie.

We invite you to subscribe to the free Little House on the Prairie newsletter for more interesting stories, news, and events, and inspirations.

Susan is an educator, researcher, and author with a love for American history and children’s literature. Her parents introduced her to Laura Ingalls Wilder in elementary school and Susan has passed on that legacy to her own family. Susan lives in Colorado Springs with her husband, Mark. She has six children and three grandchildren. Susan can be contacted at pmt2810719@gmail.com.

This was a lovely bit of information. I have loved Little House books for like….ever. I look forward to introducing them to my granddaughter in a year or so (we’ve read the picture books)

thank you for great research😀

I am so grateful for Dr. Tann! He undoubtedly saved many, many lives during his career!

Thank you, Dr. Tann!

I woke up this morning feeling crappy from Lyme disease. Every once in awhile, I think of “Fever and Ague” because that’s what I remember most of all of the books, and I remember that it was malaria, even though folks thought that it was the melon (Pa knew it wasn’t because they hadn’t eaten any prior to getting sick). So he sat down and ate a melon and Ma was pissed! Anyway, when they were sick, Laura crawling across the floor with water for Mary, and the dog bringing the doc. I love this extra history about the doctor and that people had such respect for him at a time when Blacks did not get respect. It was nice to see that on the prairie, people might have seen things a little differently.

Thank you for this interesting information on Dr Tann.

Thank you. It is interesting to learn more about Dr. Tann! I too am amazed at the courage and grit of the pioneers of the American west! The more I learn about the feat of extraordinary westward expansion the more I am convinced it could only have happened because it was divinely ordained.

Such good and great person Fr. Tann was, to many times regular people are not look at as great! Seems many feel greatness is for wealthy ppl that can buy there legacy for history to remember falsely. I am 60 and lived in Colorado for 22 years, and still amazed at the will of the people that settled the west and mid west. They had to be mentally Strong to do it.

I am watching season 9 of little house right now and was looking up something about the show. I stumbled on this and I am grateful. We went to Laura’s home in Missouri a few years back and it was cool. God bless America.

Thank you so much for this wonderful post! It was really interesting reading about Dr. Tann.

What a beautiful blog post. I’m so happy I stumbled upon it! The children’s photos bring Dr. Tann’s story to life!

Don’t make excuses for failure, just find a way for success

I enjoy your blog so very much! Thank you for your time in writing and keeping the Little House inspiration alive! keep up the good work!

I don’t know why I thought of Dr. Tan this morning, but I am glad you wrote on him.. all i could think of was his white toothed smile and NEEDED to know if he was real.. I’m so glad he was and his story was remarkable.. I wish there was more to know, it seems as though he was an incredible man..

We have to remember that the books are not toted as pore autobiographies, but stories she wrote for children that she embellished or filled out for us and it doesn’t make them any less wonderful to me, I read them as a child and I am reading again for pleasure.

I thought Laura Ingalls was born in 1867? If so, then the well-intended memorial sign should have stated that Tann doctored their family in 1873 at the earliest. Laura would have been about six when they were stricken with malaria, and she brought the water to bedridden Mary. (I am aware that Carrie was born in Kansas, but had no idea that it was Dr. Tann who delivered her! Where history is altered big-time is in ‘Farmer Boy’; there were actually large age gaps between Almanzo Wilder and his five siblings.)

Little House on the Prairies depicts events that actually occurred before Carrie was born (she was delivered by Dr. Tann in real life) so Laura was actually about three during their time in Kansas – therefore the date of 1870 is correct. She altered the timeline for continuity from her first book, Little House in the Big Woods, which necessitated including Baby Carrie, making Laura about 6 in the book.

Lovely article = only one quibble. Since Carrie was born back in the Big Woods of Wisconsin, wouldn’t it have been Grace who Dr. Tann delivered?

That’s what I was thinking.

It’s always fun and interesting to find out more about some of the lesser-mentioned characters in Mrs .Wilder’s books. Thanks for the loving care you and your family put into making this information available to those of us who loved and continue to love the Little House books.

Thank you so much for this information. As a physician and amateur medical historian my curiosity was piqued when I read about Dr Tann while reading “Little House on the Prairie” to my daughters. Fascinating man!

Only thing I’m not understanding here is how it says he delivered baby Carrie. Carrie was already born back with the family was still in the big woods in Wisconsin. According to books and mist historic documents, anyway. Surebtysts not Grace they’re talking about in this article? Anyway, Dr Tann was certainly an amazing doctor. They were few and far between in those days.

Carrie was not born in Wisconsin. She was born in Kansas.

The books are not completely accurate. The family lived in Wisconsin, then moved to Kansas and then moved back to Wisconsin before the move to Plum Creek. So the actions in Little House in the Big Woods technically take place AFTER those in Little House on the Prairie. Laura would have been too young to remember the family’s first stay in Wisconsin.

No, Carrie was not. Please read CAROLINE, Little House Revisited.

Your children are lovely and I’m so glad they dressed in historically accurate clothes. I had been looking for more information about Dr. Tann because I had read about him in the Little House book but no further information was given. I had read that it was meningitis that caused Mary’s blindness and I was wondering if Dr. Tann had helped during that illness. Regardless, your article was fascinating.

God bless people like Dr. Tann!

I homeschool my 9-year-old son and we’re working our way through this series throughout the summer, and I am loving this site and this story. Thanks so much for this!

I enjoyed reading this so much! I to love history. It fascinates me still. You can not be to old to learn new and marvelous things. Thank you.

Thank you for writing this….I am glad to know more about him, but I gotta say: What an unfortunate headstone. He did so much more than just doctor a single white family. He was a black doctor in the late 1800’s, with children, employees, properties, and multiple businesses. No mean feat.

I agree!!

This was wonderful! I love American history–in particular, the history of the average ( in reality–not so average) people that did not make it into the history books. One day, we will all become part of ‘history.’ While extraordinary things may be happening in one’s country or the world, most of us simply do our best to work, celebrate our family milestones (births, graduations, marriages and deaths) and dream of our children’s future. For me, ever since I was a child, it has been interesting to read about people who lived and loved and died in relative obscurity as national and international events whirled around them. Therein lies the ‘real’ American history.

Hi I love the storyline of Dr. Tann, Little House on the Prairie is and has been a long time favorite. Thanks for the newsletter.

Thank you for sharing this interesting story! What an amazing man. I wish someone would write a book about his life and practice.

You did a lovely job in every regard honoring this wonderful man. Thank you!

Where in Pennsylvania did Dr. Tann and his family hail from? I would be interested in knowing as I am from Pennsylvania and my family has lived in the Lycoming County area for a couple of generations.

Michelle, The Tanns lived in Washington Township, Lycoming County, PA in the 1850 and 1860 census. A PA death certificate for one of the daughters list the father Bennet Tann’s birthplace as unknown, but the mother Mary Lowe Tann was listed as being born in Philadelphia. This is probably correct because the family was living in White Marsh, Mongomery County, PA (near Philadelphia) in the 1830 census. Bennet’s will bequest to two daughters was property in Washington Township, Lycoming County, PA so they must have married and remained in PA. Bennet’s death was about 1874 based on his will, but he is listed in the 1875 Kansas census.

Love the show, the books, and the name…heehee!

Loved this so much! Thank you for the amazing history lesson to correspond with Laura’s life 🙂 Will read this to my kids as we finished last year reading through the entire Little House series as part of our homeschool read alouds!

Susan, I love how you engaged your children in the research of the real Dr. Tann behind Laura’s LHOP story. Enlightening!