It was a faith that made one humble, and a little ashamed…

Rose Wilder Lane, “The Children’s Crusade,” Good Housekeeping, November 1920.

In the spring of 1920, not long after “The War to End War” staggered to its empty close, Rose Wilder Lane boarded the ship St. Paul in New York and steamed for Paris. Recently divorced, hungry for new adventures, and seeking to supplement her income as a freelance writer, Rose had accepted a position as a special correspondent for the Red Cross. Her job was to report on the massive and unprecedented American relief efforts taking place in countries devastated by scorched-earth warfare. It was a significant chapter in the story of the Wilder women. As Rose’s quest to understand postwar Europe fueled her intellectual fire for history and political philosophy, Laura Ingalls Wilder transformed her daughter’s experiences into material for her own newspaper column, flexing her imagination and transporting her rural readers far from home.

Rose Wilder Lane in San Francisco at the outbreak of the World War I. Photo Courtesy of Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum.

Like her grandfather, Charles Ingalls, Rose’s life would be defined by what her mother once wryly described as Pa’s “wandering foot.” [1] Rose had inherited several of her grandfather’s personality traits – intelligence, recklessness, curiosity, and wanderlust among them – but Charles Ingalls’ pioneer experiences on the frontier paled in comparison to Rose’s dangerous work in Europe and the Near East. From Germany to the Balkans, Rose trekked through ruined cities awash in mud, refugees, and orphans. Her work took her as far as Soviet Russia (where she was arrested by the Cheka, the state secret police) and Muslim Albania, but nothing prepared her for “Starving Armenia,” where Lane turned the camera on what she saw, creating an indelible photographic record of the century’s first genocide. [2]

Rose in Red Cross uniform near Warsaw (1921), taken “at the time of the Bolshevik drive on that city,” according to a contemporary newspaper account. Photo Courtesy of Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum.

Based at the American Red Cross Headquarters in glittering, jazz-age Paris, Rose bobbed her hair, slashed her skirts, spent money like water, and joined an elite literary circle that included fellow travelers Dorothy Thompson, Sherwood Anderson, Edna St. Vincent Millay, and Sinclair Lewis. But for Rose, the champagne, cigarettes and clever conversation came to a sobering halt whenever she left on assignment. Thousands of readers followed Rose’s travels in “Come with Me to Europe” and “Where the World Is Topsy-Turvy,” her serial columns for The San Francisco Call and Post. Rose’s dispatches from defeated Vienna still make for compelling reading: the city was starving; factories had been shuttered for years; children in filthy rags and gunnysacks clung to women who “besieged” the gates of the children’s clinic. [3]

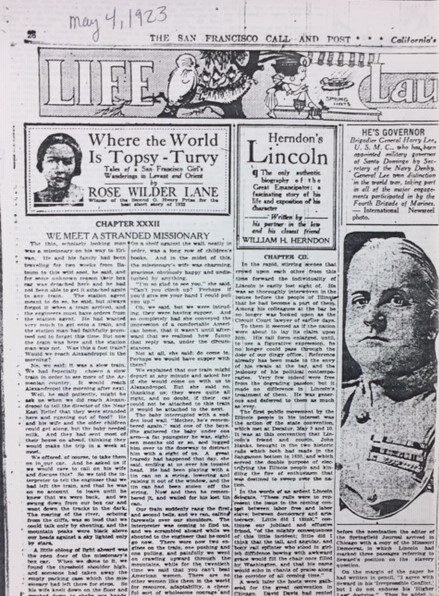

Rose Wilder Lane’s “Where the World Is Topsy-Turvy” column for The San Francisco Call and Post. Image courtesy of Sallie Ketcham.

Rose, who had given birth to a premature, stillborn son in 1909, was so disturbed by the suffering of Europe’s war orphans that she considered adopting one herself. [4] In Assisi, accompanied by children from the local orphanage, she “walked the rough-hewn cobbles St. Francis had trod,” to an ancient painted church. “See,” the children told her, pointing to pictures of Francis scolding the ferocious wolf, talking with the birds, and giving his cloak to a beggar. “He is our Saint Francis, who loved all sad people and was good to them, like the Americans.”

“It was a faith that made one humble, and a little ashamed,” Rose told her readers, moved by the children’s unwavering belief in American generosity. [5] In Europe, Rose was beginning to re-evaluate America; when she returned to America, Rose would re-evaluate both Europe and the place she called home.

Back on Rocky Ridge Farm near Mansfield, Missouri, Laura Ingalls Wilder followed her daughter’s field reports and personal letters with intense interest. Laura had supported the Red Cross throughout the war, as had countless women on the home front: knitting socks, sewing layettes, or attending fundraising auctions. In an early instance of mother-daughter collaboration, Rose’s exotic travels became the subject of several of her mother’s Missouri Ruralist columns in 1920 and 1921: “Now We Visit Bohemia,” “We Visit Paris Now,” “We Visit Poland.” [6]

There would be no colorful Missouri Ruralist column on Rose’s mission to Armenia.

The youngest victims of the Armenian genocide. In 1922, NER orphanages housed tens of thousands of infants and children. Despite millions of dollars in public and private assistance and a massive, well-coordinated effort on the ground, NER workers were overwhelmed by the size of the crisis. Photo Courtesy of Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum.

During the war, virtually every American was aware of the “Starving Armenians,” the world’s rallying cry for humanitarian intervention. Only gradually did western nations become aware that something unthinkable – the annihilation of an entire civilian population – was taking place on the Anatolian plain. In a 1918 column, Laura threw her usual decorum to the wind as she raged against the treatment of women during the war. “Every war is more or less a woman’s war, God knows, but is this in an especial way a woman’s war?” she demanded. “Never before in the history of the world has war deliberately been made upon the womanhood of the world,” she wrote, decrying the “horror and cruelty” inflicted upon the women of Armenia. [7]

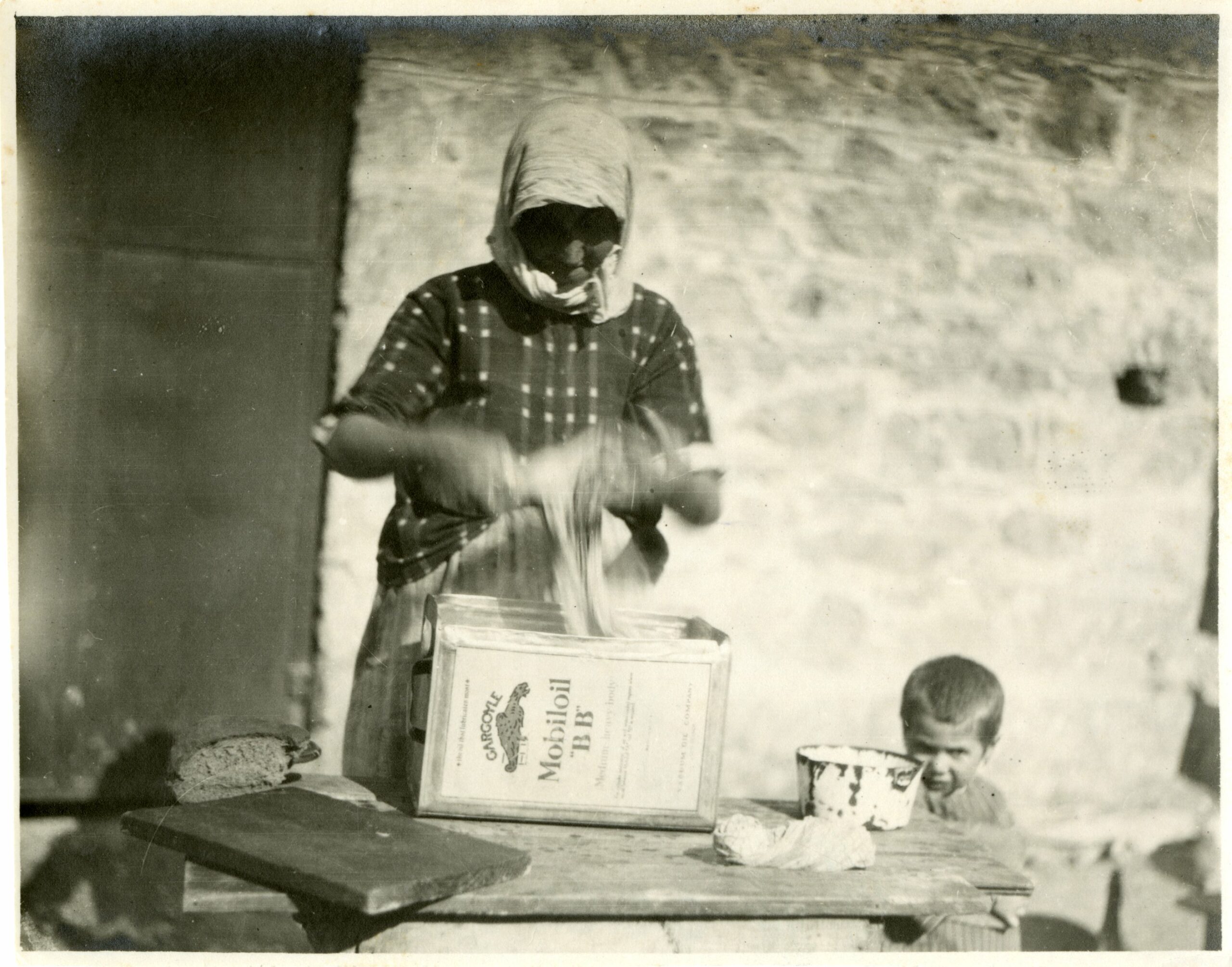

Making the daily bread ration in an oil can. Photo Courtesy of Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum.

In 1922, after accepting a new assignment with the Near East Relief (NER), Rose left for Armenia with close friend and photographer Peggy Marquis. Laura had every reason to fear for the safety of her headstrong daughter. As Rose traveled south through countries rocked by revolution, she penned a note to her grandmother in South Dakota, “Mother says that you were worried about my being in Constantinople when the Near East situation blew up.” Don’t be concerned, she insisted. “I’ve been under fire so many times in Europe that I miss it when I don’t hear rifle-fire or machine guns for a long time.” [8] It’s unlikely that Caroline Ingalls found this explanation very reassuring.

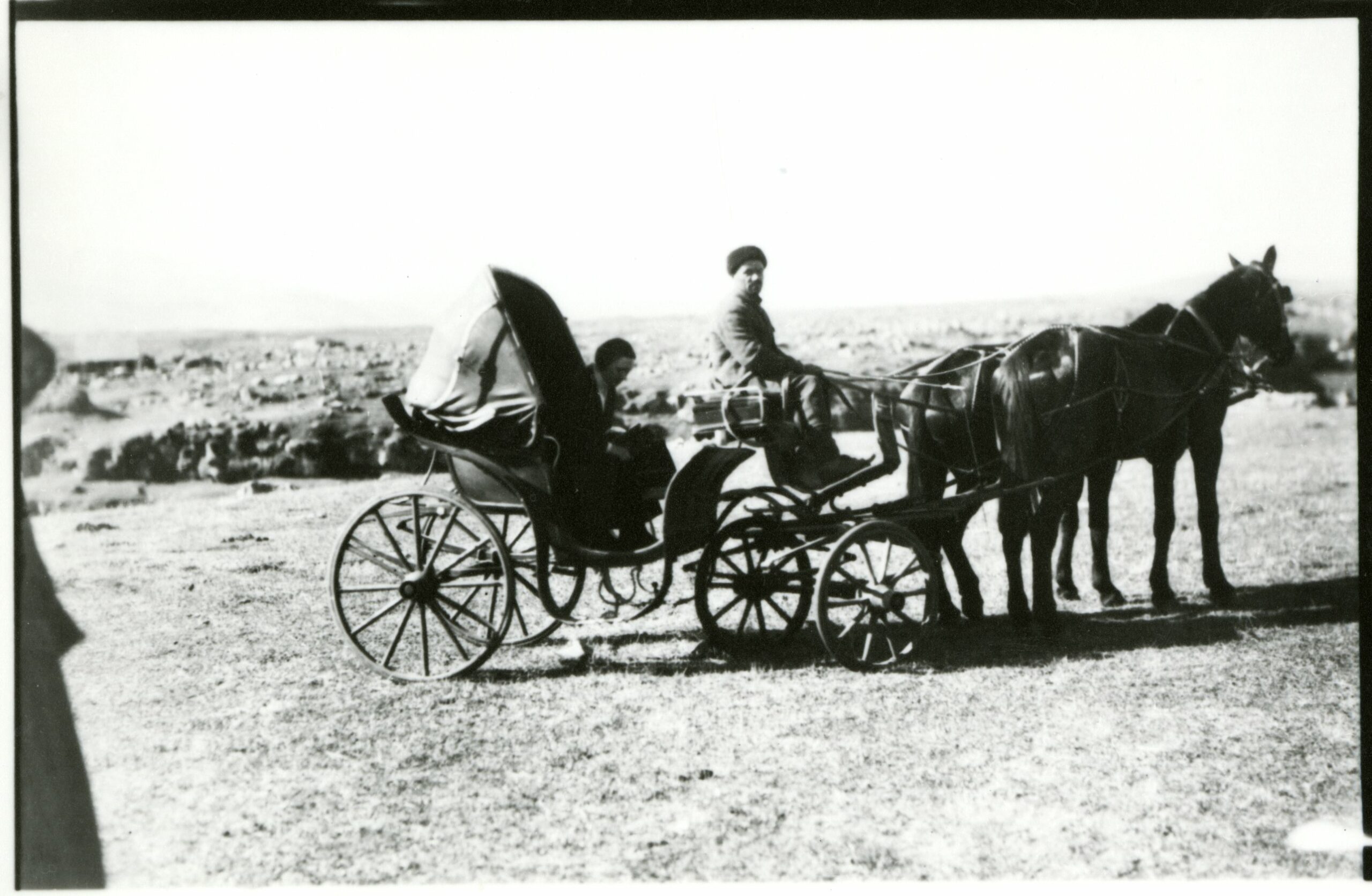

The war left many Armenian roads impassable. Rose frequently traveled by buggy with her Tatar driver (and occasionally by camel cart). Photo Courtesy of Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum.

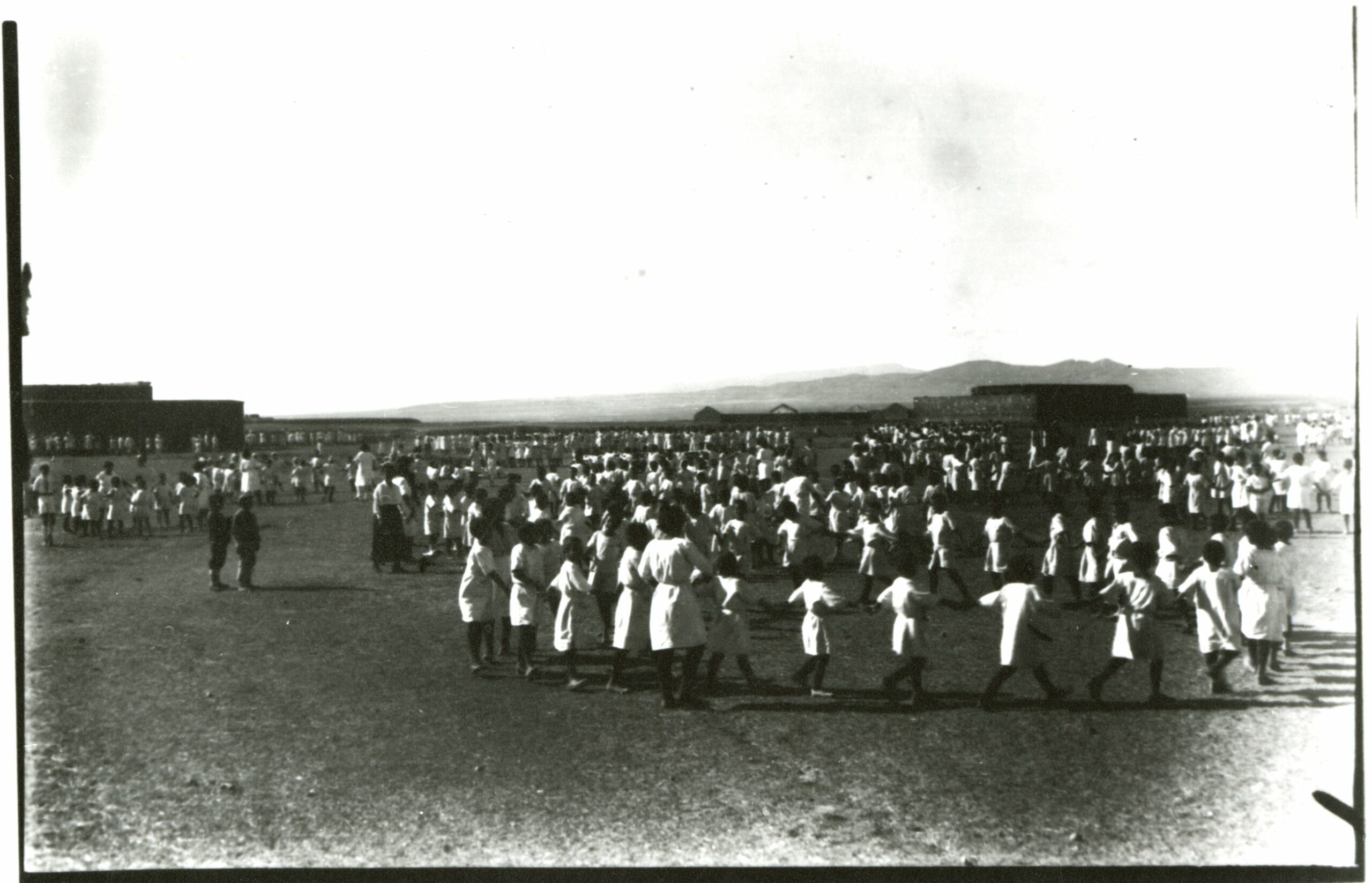

Privately, years later, Rose confided her true feelings to editor Fremont Older. “It was in Armenia,” she admitted, “that I learned fear.” [9] Rose’s journal entries depict a wasteland. “We have passed some refugees living in tepees made of cornstalks.” Other survivors lived in underground “dugouts” made of rock debris from deserted, mined villages. [10] In Alexandropol – Armenia’s Orphan City – America’s Near East Relief was housing over 30,000 children in a former Russian barracks.

Orphans dancing at Alexandropol, Armenia’s “Orphan City.” Photo Courtesy of Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum.

Like Dorothy Gale of Kansas, Rose’s thoughts increasingly turned toward home. “I was never especially patriotic at home; I rather stressed America’s faults. I was quite willing to believe that there was art in France and democracy in England and efficiency in Germany and a beauty of living in all of them that we did not have,” she wrote. Yet any American, she contended, would be “twice as patriotic as he is if he could see with his own eyes what Americans have done in Armenia.” [11]

Armenian orphans wearing outfits provided by the NER, typically the only clothing the children possessed. Photo Courtesy of Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum.

Even so, Rose’s epic journey was taking its toll: she was weary, discouraged, and she longed for home. When she looked at the Armenian landscape, she saw “miles of prairie, barren as the sea” dotted with villages that looked “exactly like prairie-dog cities, breaking through the stubble.” [12] The pickles she gratefully ate in an Armenian dung hut were watermelon pickles “such as mother still makes.” [13] Rose left Armenia in the fall of 1923, planning to cross Asia en route to San Francisco. However, in Baghdad, she turned on her heel and set a course for Rocky Ridge.

It was Christmastime when Rose finally reunited with Laura at the Mansfield train station. To Rose, seeing her mother standing on the platform, waiting for her, was “like a dream.” [14] The prodigal daughter had come home.

Recommendations from the website editors

Sallie Ketcham wrote an interesting book entitled Laura Ingalls Wilder: American Writer on the Prairie and contributed a fascinating essay to Pioneer Girl Perspectives: Exploring Laura Ingalls Wilder called “Fairy Tale, Folklore, and the Little House in the Deep Dark Woods.”

There have been many interesting books written about Laura Ingalls Wilder and her daughter and editor Rose Wilder Lane. We invite you to visit our Recommended Reading lists for children and young adults and adults.

You may also be interested in documentary film about Laura Ingalls Wilder.

Be sure to subscribe to our newsletter for more inspired articles from various authors!

Notes:

1. LIW, These Happy Golden Years, Chapter 16 “Summer Days,” p. 138.

2. Rose Wilder Lane and Peggy Marquis’s haunting, rarely-seen photographs are preserved on fragile glass-plate negatives at the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library. The photos, along with Rose’s eyewitness columns and feature articles, are particularly valuable to students and scholars of the Armenian Genocide.

3. RWL, “Come With Me to Europe,” San Francisco Call and Post, April 2-16, 1921.

4. RLW letter to Berta Hader, Sept. 7, 1920. RWL Papers, Herbert Hoover Presidential Library (HHPL).

5. RWL, “The Children’s Crusade,” Good Housekeeping, November 1920.

6. LIW, The Missouri Ruralist, September 5, 1920; January 5, 1921; February 15, 1921.

7. LIW, The Missouri Ruralist, “What the War Means to Women,” May 15, 1918.

8. De Smet News, undated article (1923). Albania Correspondence 1926-1927, William Holtz Papers, HHPL.

9. RLW to Fremont Older. Fremont Older Correspondence. July 14, 1928. RWL Papers, HHPL.

10. RWL, Journal, September 28, 1922. RWL Papers, HHPL.

11. RWL, “Where the World is Topsy-Turvy,” San Francisco Call and Post, May 30, 1923.

12. RWL, “Where the World is Topsy-Turvy,” San Francisco Call and Post, May 14, 1923.

13. RWL, “Where the World is Topsy-Turvy,” San Francisco Call and Post, May 21, 1923.

14. RLW, Journal, Dec. 20, 1923. RWL Papers, HHPL.

Sallie Ketcham is the author of Laura Ingalls Wilder: American Writer on the Prairie (Routledge, 2014). Her essay, "Fairytale, Folklore and the Little House in the Deep, Dark Woods," is included in Pioneer Girl Perspectives: Exploring Laura Ingalls Wilder (South Dakota Historical Society Press, 2017).

I’m a huge fan of the Ingalls, Wilder families. Love books, cookbooks and tv show. I love learning about the real Ingalls and Rose was one strong woman. Will look forward to reading more. Donna Young

Beautiful! Thank you!