In the history of literature, there’s nothing quite like the relationship between Laura Ingalls Wilder and her daughter, the journalist Rose Wilder Lane. One of the most remarkable things about the Little House books is how the series grew out of their profoundly close and often contentious relationship. From the beginning, the books were the outgrowth of a unique mother-daughter, writer-editor team as Laura and Rose labored together to transform the older woman’s handwritten originals, famously inscribed in pencil on dimestore tablets, into beautifully edited and finished books. While the writer-editor bond is often fraught—and sometimes an emotional battlefield—it almost never involves such close relations.

Scholars have long known that Laura drew from memory and drafts of her then unpublished 1930 memoir, Pioneer Girl, to write those initial manuscripts. But what hasn’t been as well understood is how the editorial process between mother and daughter evolved. In fact, the two women began developing their tentative pas de deux years earlier, almost as soon as Rose Wilder herself became a writer. In 1908, Rose published her first article in the San Francisco Call under her maiden name, and over the next few years, began urging her mother to buy herself a used typewriter on an installment plan and get to work writing for newspapers herself.

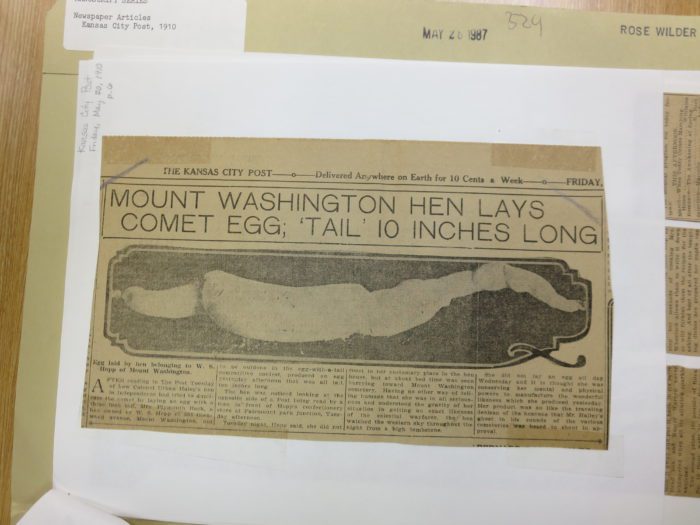

Laura heeded that call. In 1910, Rose was in Kansas City penning outlandish pieces inspired by the yellow press for The Kansas City Post, breathlessly reporting that a hen inspired by Halley’s Comet had laid an egg with a meteorically long tail. That same year, her mother, “Mrs. A. J. Wilder,” was covering the poultry beat from a more conventional angle, with “Profits of the Good Fat Hen.” While her daughter was selling real estate in California, Mrs. Wilder was offering sage counsel to rural Missouri women eager to succeed with finicky flocks of barnyard fowl in such pieces as “Judgment Needed With Late Chicks.”

Article from The Kansas City Post, May 20, 1910, believed to be written by Rose Wilder Lane. Herbert Hoover Presidential Library.

Her topics were modest and her voice humble, but this would nonetheless prove to be an extraordinarily fruitful period for Laura, resulting in her crisply confident manifesto, “The Small Farm Home,” promoting the joys and rewards of a five-acre spread, first delivered in January, 1911, at the Missouri Home Makers’ Conference, part of the highly-popular and well-attended “Farmers’ Week” at the University of Missouri’s new College of Agriculture in Columbia. Although Laura herself could not attend in person, her tribute to small farms and little houses was well-received by at least by one attendee, John Case, editor of the Missouri Ruralist who re-printed it the following month, launching Laura’s long association with the influential farm paper.

We don’t know exactly how involved Rose was in her mother’s work during this early period, but surviving fragments of letters suggest that she was always directing and encouraging her. “Why don’t you write up Mansfield,” Rose wrote at one point, urging her mother to capture the local color of an “Aid society oyster supper” in the Ozarks. Indeed, in coming years, Laura would adapt such advice to suit her own voice in her Ruralist columns, compiling an intimate portrait of regional farm life.

Yet the women always had larger ambitions: Sometime in 1914, Rose wrote her mother suggesting that she recover a letter that Laura had written to her mother, Caroline Ingalls, and her sister Mary. Rose instructed Laura to transcribe that letter and insert it “verbatim into that ‘story of my life’ thing” that Laura had apparently already embarked on. The remark revealed not only a cozy editorial familiarity between mother and daughter but the ways in which roles were being reversed, with Rose adopting the role of teacher and coach, Laura falling into the role of pupil.

Most significantly for their later work, in the late summer and fall of 1915 Laura took a front row seat as Rose’s career vaulted into high gear. During several years apart, the women had been diligently trying to scrape together funds so that the Wilders might visit San Francisco for the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, the world’s fair celebrating the city’s restoration after the 1906 earthquake. In the end, money was so tight that only one of the Wilders—Laura—would be able to make the trip.

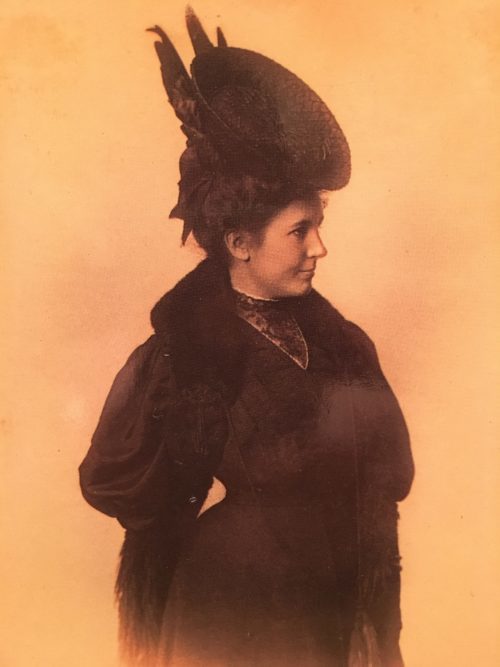

Laura Ingalls Wilder on a visit to Kansas City to see her daughter, circa 1906. Herbert Hoover Presidential Library.

The letters she sent home to her husband Almanzo, later published in West from Home: Letters of Laura Ingalls Wilder, San Francisco 1915, capture the visit, one of the most consequential of her emerging writing career. And of course she had fun, in the first vacation she’d ever taken in her life, revelling in the sights, sounds, smells, and tastes of the Exposition, stuffing herself with hot buttered scones and marveling at the “Tower of Jewels” and the fair’s nightly fireworks. She toured the city by streetcar and the Bay by ferry, recording the joys of wading in the Pacific Ocean. In the city’s restaurants, she took particular delight in eating her fill of seafood.

But she had arrived with a more serious purpose, fully intending to apprentice herself to her daughter, a newly-minted editorial assistant at the San Francisco Bulletin, hired earlier that year by her friend and former roommate, Bessie Beatty. Laura assured Almanzo that she had come to the big city to make money, planning to write about the Exposition for the Ruralist, telling him, “I am not for a minute losing sight of the difficulties at home or what I came for. Rose and I are blocking out a story of the Ozarks for me to finish when I get home….I am learning so that I can write others for the magazines. If I can only get started at that, it will sell for a good deal more than farm stuff.”

Rose Wilder, Kansas City, circa 1906. Herbert Hoover Presidential Library.

That process of “blocking out” stories would establish their lifelong habit of close collaboration, with Laura listening to her daughter’s editorial counsel on how to craft columns, magazine articles, and ultimately the memoir that would provide the scaffolding of the Little House books. All the while she was growing accustomed to accepting Rose’s extensive editing. Steeped in the ways of the yellow press, Rose would funnel her own energies into fabricated celebrity “autobiographies” and commercial fiction. But her mother would pick and choose from the smorgasbord of professional opportunities and the advice her daughter laid before her, eventually transforming her memoir into novels for children. In the end, that choice would indeed “sell for a good deal more than farm stuff.”

Recommendations from the website editors

Caroline Fraser was awarded the 2018 Pulitzer Prize in Biography for a fascinating new book entitled Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder. The Pulitzer Prizes organization described Prairie Fires as “a deeply researched and elegantly written portrait of Laura Ingalls Wilder, author of the Little House on the Prairie series, that describes how Wilder transformed her family’s story of poverty, failure and struggle into an uplifting tale of self-reliance, familial love and perseverance.”

Caroline also contributed an interesting essay to Pioneer Girl Perspectives: Exploring Laura Ingalls Wilder. For readers interested in natural history, we recommend Caroline’s Rewilding the World.

There have been many interesting books written about Laura Ingalls Wilder and her daughter and editor Rose Wilder Lane. We invite you to visit our Recommended Reading lists for children and young adults and adults.

You may also be interested in a documentary film about Laura Ingalls Wilder.

Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder by Caroline Fraser

You can learn more about Prairie Fires by reading our brief book summary and visiting the author’s website and Facebook page.

Caroline Fraser is the author of Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder, one of The New York Times' 10 Best Books of the Year, and winner of the Pulitzer Prize in Biography and the National Book Critics Circle award for biography in 2018. Fraser served as editor of the Library of America edition of Wilder's Little House books and has written for The New Yorker and The Atlantic, among other publications.

How many years different was Laura n Alonzo? Mary ever get married and go to a blind school? Was there ever an Albert?

About 10 years between them. No mary never married. And there was no Albert.

Mary never got married. She did goto the blind school yes.

It still exists this school by the way.

No there never was an Albert.

I have a post card with her picture I was wondering about it

I have done some research, and I cant figure out what Rose’s middle name is. All of the articles about her call her Rose Wilder Lane, and I would just really like to know what her middle name really is.

Enjoyable issue and helpful bibliography. Still wish more people would read Laura’s own words and judge her by that rather than by someone’s else’s opinion. Her fascinating adult views are well-represented by her Missouri Ruralist columns.

The stories were Laura’s, Almanzo’s and those of both the Ingalls’ & the Wilder’s but – apart from her final published diary entries – all were reworked through Rose’s typewriter before publication.

Mellissa Gilbert may have been actually related. The resemblance is un canny!

Fraser’s book is excellent. It goes into detail what was happening around the country socially and politically, so you get a better understanding for the decisions people were making, especially the Ingalls and Wilders. Also some new photos that I had never seen.