Once upon a time, sixty years ago, a little girl lived in the Big Woods of Wisconsin, in a little gray house made of logs.

—Little House in the Big Woods

Scholars of myth, child psychology and literature as diverse as Joseph Campbell, Bruno Bettelheim and Marina Warner argue that, ultimately, the primary purpose of myth and fairy tale is not “useful information about the external world, but the inner process taking place in the heart and mind of a child.” (1) In effect, fairy tales help guide children over the threshold of childhood into the strange, often baffling world of adulthood, bestowing words of reassurance and words of warning along the way. Classic myths and fairy tales cross all settings and cultures: Homer’s wine-dark sea becomes Hans Christian Andersen’s cold Danish ocean – and the steppes of Russia with its howling wolves, the ghost-haunted mountains of Japan, the Black Forest of the Brothers Grimm. And it is also Laura’s western frontier, her prairie proving ground, the “sacred space . . . where you can find yourself over and over again.” (2)

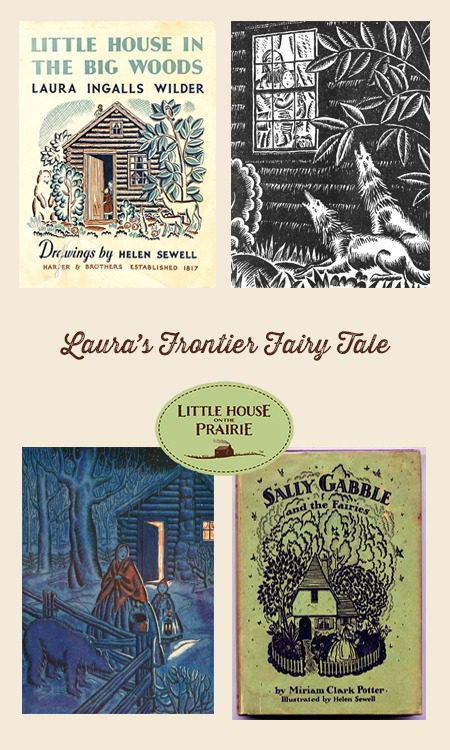

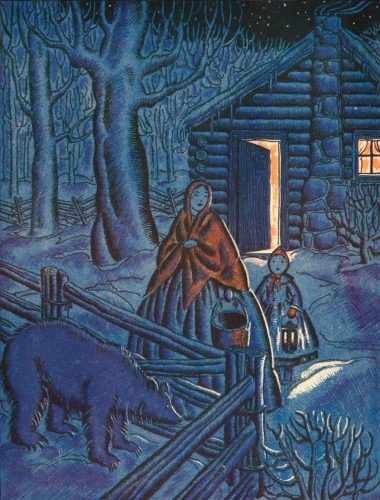

Little House on the Big Woods Cover - Illustrated by Helen Sewell

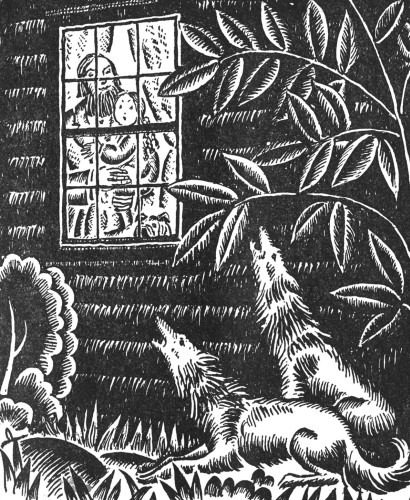

Most notably in Little House in the Big Woods (the most episodic book of the Little House series) but to varying degrees in all of her novels, Wilder drew heavily upon traditional elements of fairy tale, folklore and the archetypal hero’s journey to engage young readers and draw them into her lost world. Like Little Red Riding Hood, Laura lives in a lonely cabin in the darkening woods, where wolves “that eat little girls” prowl just outside the walls. Pa is The Huntsman and The Woodcarver who makes wonderful gifts for Christmas. Ma is good and gentle and kind. Like Snow White and Rose Red, dark Laura has a fair-haired darling sister, Mary. Wild bears, stalking panthers and talking owls haunt the woods at night, but Pa’s magic fiddle dispels the fear and the darkness. Sleigh-bells ring out in the frosty air as beautiful young women pile into cutters and race over the snow to a glorious “sugar ball,” the great celebration of the maple sugar harvest. Naughty, sullen receive their just rewards – like young cousin Charley, who cries wolf once too often and is attacked by wasps.

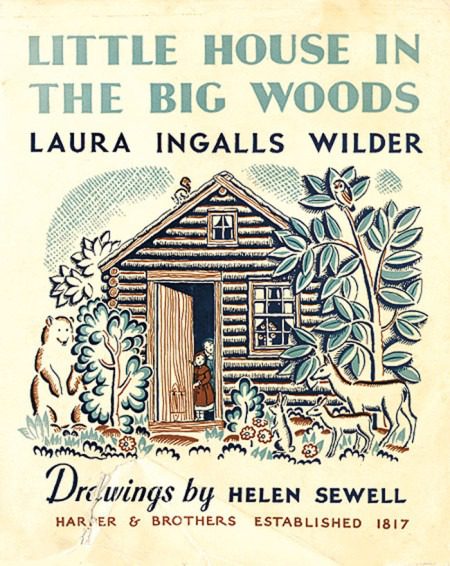

Ma in her red cape, walking with Laura. The cow and the bear story illustration!

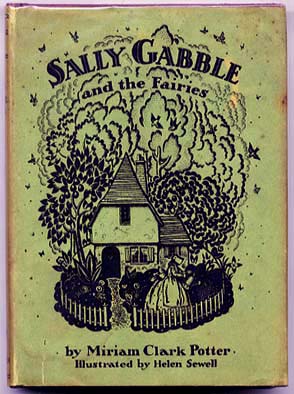

Helen Sewell, Wilder’s first illustrator, had already illustrated several fairy stories by the time she began work on Little House in the Big Woods. Sewell’s artistic style visually reinforced the fairy tale elements of Wilder’s work. When Garth Williams illustrated the 1953 edition of Wilder’s work, the artwork changed dramatically, highlighting the nuclear Ingalls family, their pioneer skills and day-to-day tasks in a dynamic style familiar to “Dick and Jane” readers.

Sally Gabble and the Fairies - Another book illustrated by Helen Sewell

Wilder’s interest in fairy stories preceded the Little House books; from childhood, her favorite authors included Tennyson and Sir Walter Scott, lyric poets who often wrote of fairies, enchantment and magic. In 1915, the year Wilder broke into children’s literature, she did so with a series of fairy poems published in the San Francisco Bulletin. As her writing matured, Wilder wrestled with her editors (and occasionally with her own daughter, writer Rose Wilder Lane) to preserve the truth of her frontier childhood: winters were hard, children went hungry, times were tough, even a beloved sister might go blind. And yet despite setbacks and hardships, the Little House series is also shot through with another defining characteristic of fairy tales – heroic optimism. In Oxford scholar Marina Warner’s words, “The more one knows fairy tales the less fantastical they appear; they can be vehicles of the grimmest realism, expressing hope against all the odds with gritted teeth . . . readers hold their breath as this mood of heroic optimism forms against the odds.” (3)

Caroline Fraser’s wonderful essay “Laura Ingalls Wilder and the Wolves” sums up the depth and the contradictions inherent in both Wilder’s work and classic fairy tales. “The Little House books have always been stranger, deeper, and darker than any ideology. While celebrating family life and domesticity, they undercut those cozy values at every turn, contrasting the pleasures of home (firelight, companionship, song) with the immensity of the wilderness, its nobility and its power to resist cultivation and civilization. In her hymn to the American west, Wilder treasures forest, grasslands, wetlands, and wildlife in terms that verge on the transcendental. Alive in Laura Ingalls Wilder’s memory of it, the wilderness she knew — now lost — continues to reflect her longing for a vanishing world, a rough paradise from which we are excluded by a helpless devotion to our own survival.”(4)

The wolves, as Laura Ingalls Wilder remembers them.

Readers who follow Wilder into the deep, dark woods do so because they trust her as their guide. Wilder’s unique, creative fusion of childhood memory, fairy tale, family chronicle, western history and love of the living prairie still resonates so strongly for so many of us today. The frontier fairytale and heroic optimism are central to her lasting appeal and her quiet art.

- Bruno Bettelheim, The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales.

- Joseph Campbell, A Joseph Campbell Companion: Reflections on the Art of Living.

- Marina Warner, Once Upon a Time: A Short History of Fairy Tale.

- Caroline Fraser, “Laura Ingalls Wilder and the Wolves,” Los Angeles Review of Books, Oct. 10, 2012.

Recommendations from the website editors

Sallie Ketcham wrote an interesting book entitled Laura Ingalls Wilder: American Writer on the Prairie. She also contributed a fascinating essay to Pioneer Girl Perspectives: Exploring Laura Ingalls Wilder.

There have been many interesting books written about Laura Ingalls Wilder and her daughter and editor Rose Wilder Lane. We invite you to visit our Recommended Reading lists for children and young adults and adults. You may also be interested in a documentary film about Laura Ingalls Wilder.

Sallie Ketcham is the author of Laura Ingalls Wilder: American Writer on the Prairie (Routledge, 2014). Her essay, "Fairytale, Folklore and the Little House in the Deep, Dark Woods," is included in Pioneer Girl Perspectives: Exploring Laura Ingalls Wilder (South Dakota Historical Society Press, 2017).

I love reading about the ingalls family and there life. Its so interesting. When I read her books I could imagine myself being right there with them. From the books I get that life was really hard on all of them not having a lot of food and being so cold in the winter and then so hot in the summer. It makes me really appreciate the things I have.

Thank you, Sally, for coining the term “frontier fairy tale” – a perfect subtitle for the entire “Little House” series of books. Wilder was a master storyteller with living truths tucked in between the history, settings and characters.