As a child, I learned my Bible lessons by heart, in the good old-fashioned way, and once won the prize for repeating correctly . . . verses from the Bible.

—Laura Ingalls Wilder

I would never have written A Prairie Girl’s Faith: The Spiritual Legacy of Laura Ingalls Wilder if Spring Ridge School hadn’t consolidated with Oak Ridge school by the mid-1950s. Such grade schools were rapidly disappearing from eastern Kansas, but that little consolidation was a last-gasp effort by a small community to keep its country school local—and for children to be let out of school after only eight months so they could help with the spring planting!

(We young scholars felt that getting out early was a great idea even though our dads may have already done the spring planting!)

Stephen in the 4th grade. Photo courtesy of Stephen W. Hines.

The resulting Victory Consolidated School allowed me access to a bigger library–four feet wide and five shelves tall–where one day I came across, first, On the Banks of Plum Creek and, later, Little House on the Prairie—and my life, at least my reading life was changed forever.

Before then, I had been pretty much of a “Dick and Jane” guy, and, later, a Silver Chief, Dog of the North fan. In our search for virtue, we turned to animals.

As far as Dick and Jane were concerned, I just didn’t know what to make of them. I didn’t think my background strange or unique; I thought their background strange and unique. They were always clean, keen, and extraordinarily well-dressed—even when playing. You were supposed to have “fun with Dick and Jane,” but they never did anything in the dirt, and their dad wore a necktie, almost all the time!

My dad came home all dirty from having worked on an oil lease and then he immediately began to feed and milk the cows. Mr. Father of Dick and Jane didn’t seem to have two jobs. So I was hoping to find something on that “large” Victory Consolidated bookshelf that made sense, and that is where Laura Ingalls Wilder and her family came in.

Victor W. Hines with his 15-month old son Stephen on the family farm near Plum Creek, Kansas. Photo courtesy of Stephen W. Hines.

When I first picked up Laura’s On the Banks of Plum Creek in the fourth grade, I realized I was back in a world I could identify with. Here was no dad with a tie but a pioneer farmer and his family. They worked in the dirt. They worked with their hands, there were chores to do—and there were songs they sang that I myself knew. They felt like kinfolk to me, rejoicing in nature and its witness to the glory of God and half afraid of it too when dark thunderstorms tore along over the Kansas prairie.

As for the songs, Pa had his fiddle, and my mother had her upright piano on which she used to practice hymns for Plum Creek Methodist Church. Plum Creek! My ignorance of geography was colossal. Surely the Plum Creek of Minnesota must be connected with the Plum Creek of Kansas that ran right by our little white-sided Methodist church. We had connections galore!

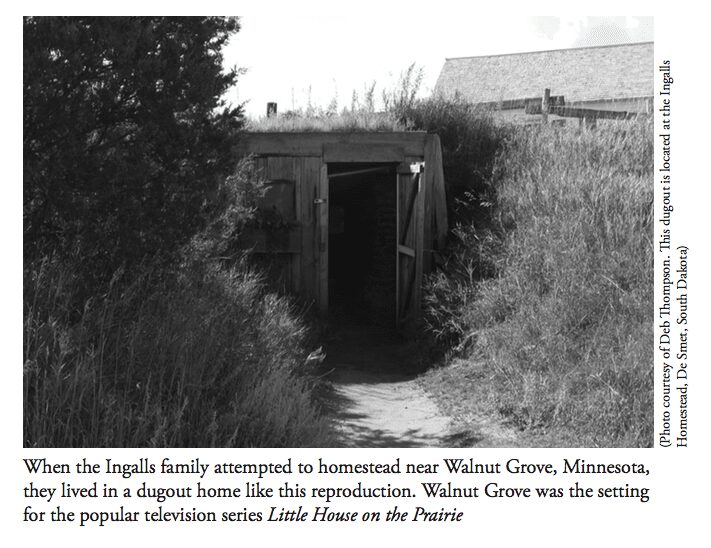

Photo courtesy of Deb Thompson

Soon I was reading the other Laura books as well. Most thrilling of all was Little House on the Prairie, which secured my everlasting interest in all things pertaining to Laura. Miles from neighbors, she watched as her Pa selected the land on which they were to build, cut down the trees that were to become the logs that shaped their cabin, and built their fireplace which was to heat the little home.

Why, from my little school room at Victory Elementary, I could look out on the very same prairie grass that greened the land which surrounded Pa’s homestead. At night I could listen to the eerie howl that coyotes have had since time immemorial, a solemn lament to the moon that shivered my spine. And I could stand by my mother’s piano and sing “Rock of Ages,” just as Laura had sung the same tune to Pa’s fiddle-raised prayer:

Rock of Ages, cleft for me

Let me hide myself in Thee;

Let the water and the blood,

From thy wounded side which flowed,

Be of sin the double cure,

Save from wrath and make me pure.

—Augustus Toplady

Without quite realizing how she had done it, I felt Laura had made her family and my family lifelong kindred spirits. I was never to lose this early interest in all things Laura, but life moves on and I became busy pursuing a journalistic career.

Although I continued to remember her children’s books with fondness, and even read all of them out loud to my librarian wife who had somehow gone clear through a master’s in library science without reading them, it was an act of serendipity that brought Laura and her family back into my life.

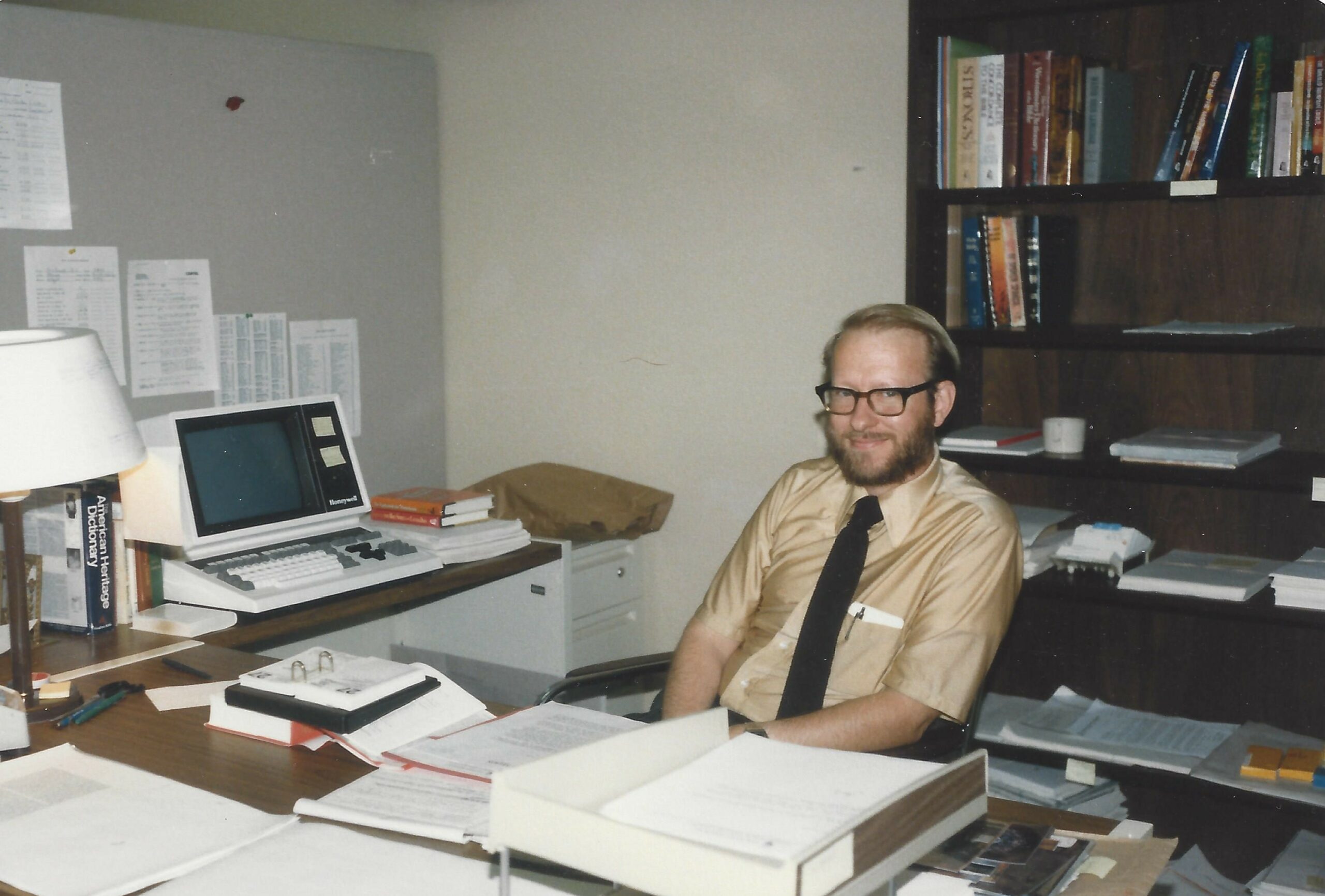

After several years with a magazine and four years with a religious book company, I found myself in downtown Nashville working for a newsletter publisher. One day on a lunch break, I idled over to the wonderful downtown bookstore, Rare, Foreign & More, and, while browsing their shelves, made a discovery.

Stephen as a young journalist. Photo courtesy of Stephen W. Hines.

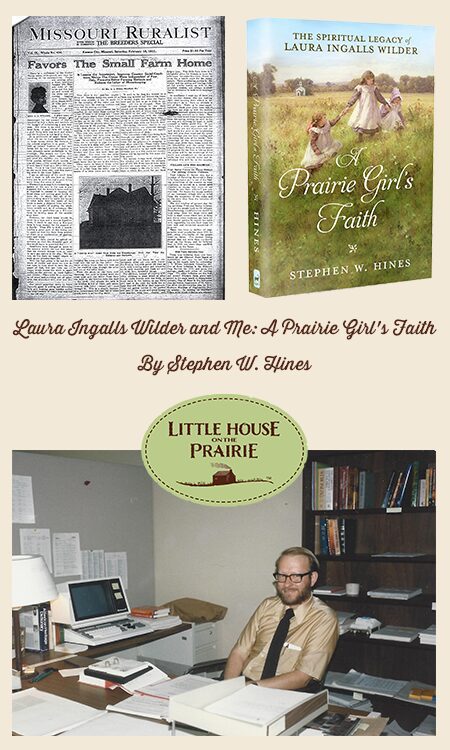

Wilder historian William Anderson had several years earlier published a wonderful title, A Little House Sampler, with the University of Nebraska Press. Once again I was hooked on the many adventures of Laura, especially on her adult adventures as a pioneer woman journalist of the early twentieth century, who had written about her life on an Ozark farm. Mr. Anderson’s book contained columns Mrs. Wilder had written for a paper called The Missouri Ruralist. Her advice to women and information on her adult life captured my enthusiasm immediately, and I wondered if there were more articles from the Ruralist that had not yet been brought to light.

The Ruralist itself, which still publishes today, did not have a complete list of all that she had done, so if I was going to find out anything more and bring that information to her fans, I was going to have to look myself. This meant that the old Horace Greeley motto—“Go West, young man, go west”—now applied to me, for the logical place to look was in the archives of the Ellis Library at the University of Missouri. With a “grubstake” from a local publisher of a few hundred dollars, I set off.

Missouri Ruralist Newspaper Column

There were two great dangers to the venture. One would be that Laura had not been given a byline by the Ruralist; therefore, her writing would have been lost because it couldn’t be identified. The second great danger was simply that the articles themselves would be so dated they would not be interesting to the modern reader.

Little did I know what a treasure I would find.

Contrary to the usual custom of Mrs. Wilder’s day—where many reporters/authors weren’t given any credit for their work–she had been given a byline; and fortunately, most of what she wrote had a universal appeal to anyone who wanted to know what the adult Laura had really been like. She was fascinating, funny, opinionated, and fully interested in the world around her.

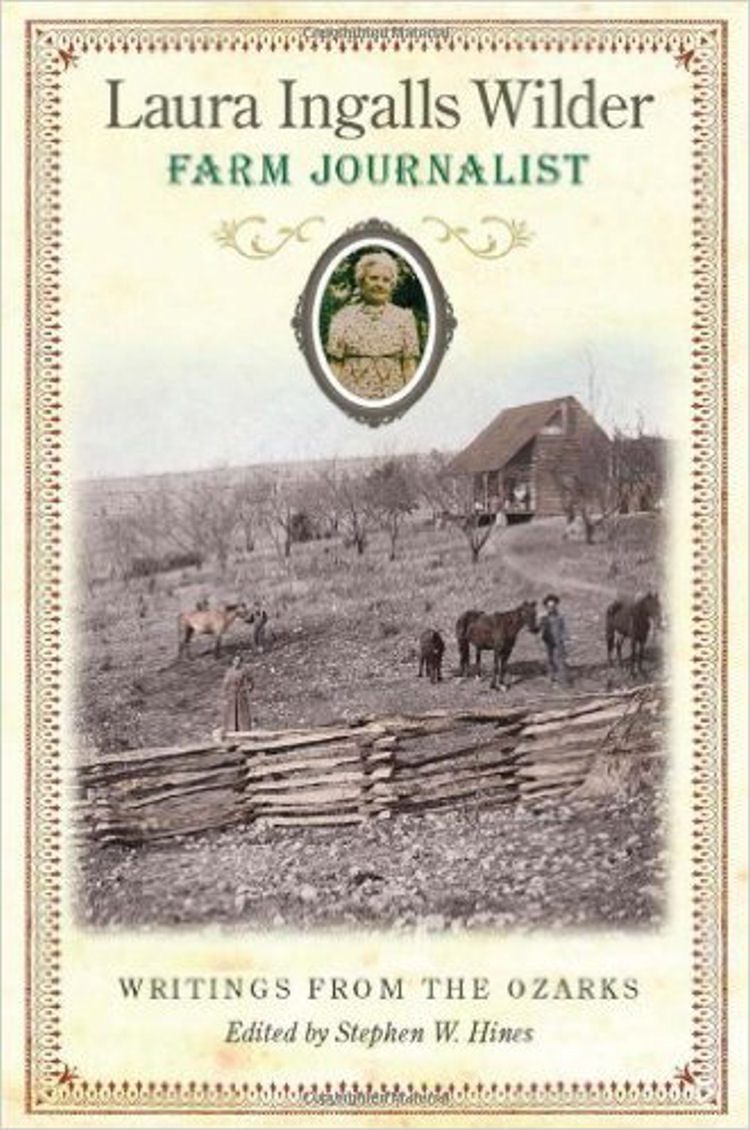

For the sheer joy, I began publishing about Laura and found readers everywhere who enjoyed her just as much as I did. The whole of my writing and editing career was changed by what this woman had written, and nine books followed, including one from the University of Missouri called Laura Ingalls Wilder, Farm Journalist, which collected all the Ruralist writings for the first time.

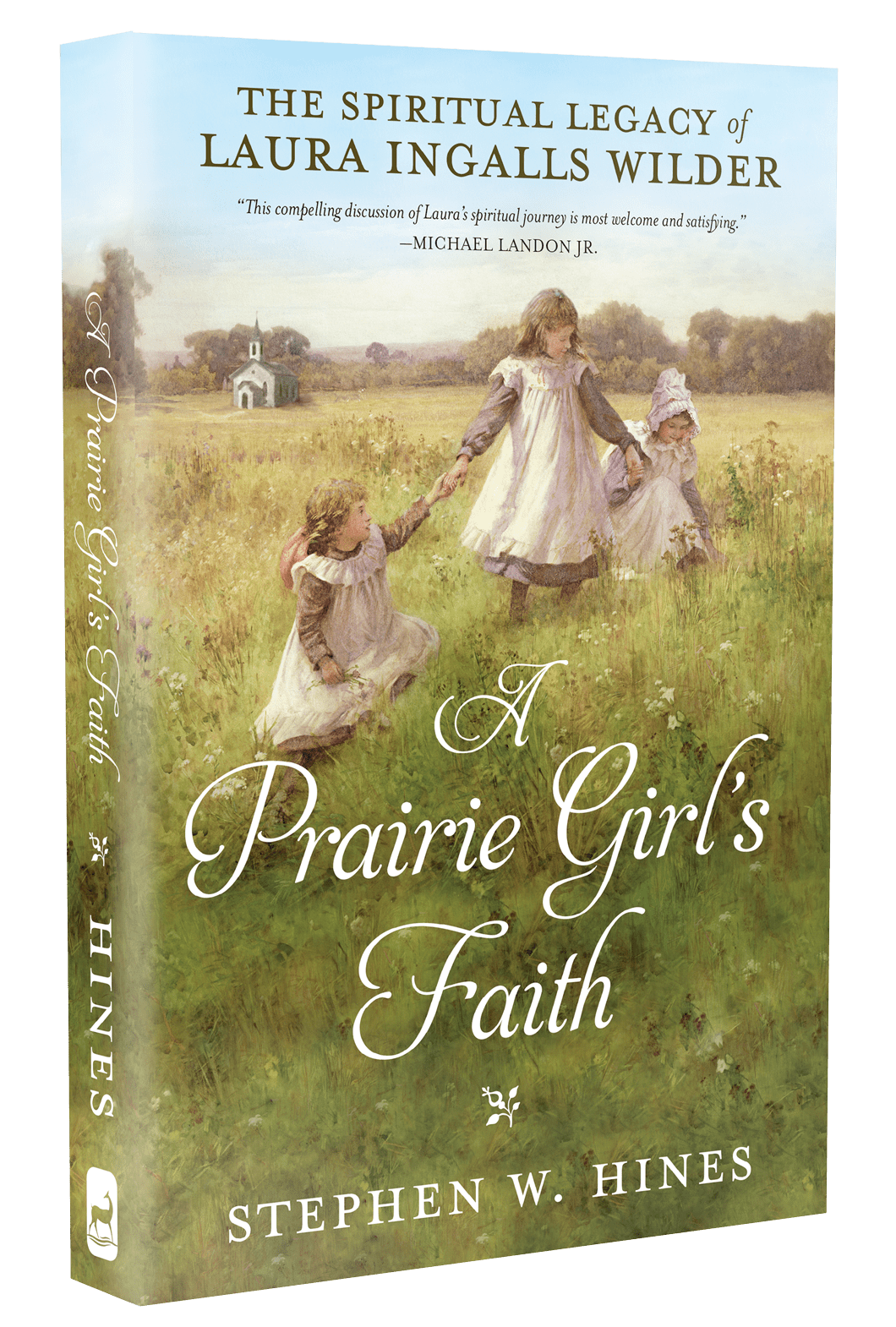

Now I have written a tenth book, A Prairie Girl’s Faith: The Spiritual Legacy of Laura Ingalls Wilder, which summarizes the most important aspects about what Laura had to teach us about life, faith, and love for one’s neighbor.

Every fan knows that the Ingalls family prayed together and stayed together. There were many outside dangers to family security and life on the prairie, but they sang their songs—many of them hymns—and faced dangers bravely and with hope. In the midst of independent values, there was also an ethic of mutual help given to each other as the need arose.

A Prairie Girl’s Faith, the only book to delve deeply into Laura’s religious beliefs, shows the Ingalls family and pioneers in general practiced “loving your neighbor as yourself” in addition to self-reliance.

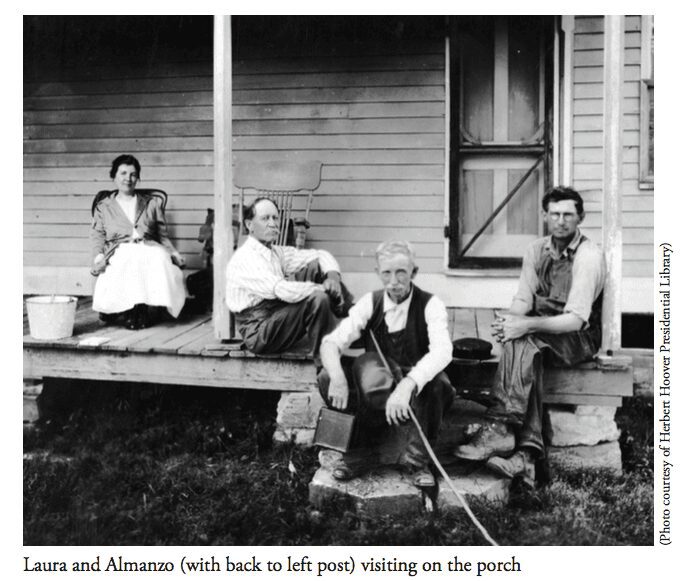

Photo courtesy of Herbert Hoover Presidential Library

There is a hilarious story in A Prairie Girl’s Faith where Laura recounts the activities of a nearby neighbor who was a “good borrower”: “He borrowed the hand tools and the farm machinery, the grindstone and the whetstone, and the harness and saddles, also groceries and kitchen tools.” Yet, in the end, when she and Almanzo were facing sickness and sorrow, they found him to be really helpful after all. The proof of love is always, in the end, on how people behave in a crisis.

At the end of World War I when people were questioning Christian beliefs because they had not prevented the terrible slaughter, Laura defends Christian values, which were her own values, by writing: “It is rather the lack of Christianity that has brought us where we are. Not lack of churches or religious forms, but of the real thing in our hearts.” She goes on to say: “So, if we are eager to help in putting the world to rights, our first duty is to put ourselves right . . . to overcome our selfishness and be as eager that others shall be treated fairly as we are that no advantage shall be taken of ourselves.”

This is but a taste of the commonsense Laura that I know. My book additionally contains reflections on the hymns by which the little family supported themselves, recipes from their church potlucks, and even a sampling of what church life was like for them as they helped found two churches themselves. Growing up with Pa and Ma built Laura’s faith, and in her adult life she put this faith into action.

May we all benefit, as I have, from this pioneer girl’s example!

Founder of Seer Green Press—from which he produces his own material—Stephen Hines has published nineteen books. Nine of these books relate to Laura Ingalls Wilder and have been published with such Houses as Bantam Doubleday Dell, The University of Missouri Press, and Thomas Nelson Publishers. Hines and his wife live in Nolensville, Tennessee, where they raised their daughters, now grown.

I just made one of the chocolate cake recipes from the Church Potluck chapter. The first one, and the frosting. The cake was moist and delicious, and I was able to get the frosting to thicken nicely. I liked how it hardened some too, so it won’t smear when I cover it. Thanks for including those lovely recipes in your fascinating book!

I can’t wait to get my copy of the book. Since last Oct. I have been doing a 1st-person portrayal of Laura to great reviews. It started as an hour-plus program for adults but has been adjusted for schools and church functions. I live about 2 hours from Mansfield and have visited there for more in-depth research. I have wanted to do this all my life and am now finally old enough to be her (60+) as of 1947. My husband did not recognize me in the costume! Just as I was preparing for a presentation at my own church, a friend sent me a copy of “Mature Living” about your book. It is truly God’s timing. I have quit working full-time, but there is now way to say I am retired! I am busier than ever and loving it. I will post after I get the book read. I am especially excited about her Bible bookmark.

If one is able to visit one of the sites where Laura lived as a youngster , one will have access to many books about her life.

Pretty soon there won’t be a book store big enough to hold all the books there are about Laura! Unfortunately, in the big city of Nashville, there is really only one major book store left that deals in new books: Parnassus.

This book is the WINNER OF THEM. ALL!!! A very true sense of Laura’s spirituality which was the driving force behind her extraordinary life. Strength of character (we know Who gave that to her) perseverance (likewise) and great sensitivity for anything alive (again WE KNOW, don’t we?). Thank you so much for digging deeper into Laura’s life and presenting TRUTH.

Except for Laura Ingalls Wilder, Farm Journalist, all the other titles are out of print, but you can generally find them online wherever used books are sold.

Living the simple life tends to be an idyllic notion for many, and lessons from Ma Ingalls, the comforting mother in The Little House on the Prairie, teaches us how to embrace the simple lifestyle we want. Recently, I picked up The Little House on the Prairie series with my daughter.

I plan to buy a copy of this treasure immediately and will be adding your other 9 titles to my future purchases.

How do I get the book

I’m afraid that if a book store is not handy, finding the book online is your best bet. Don’t give up and feel free to review it.

I HAVE ALL OF THE BOOKS. ENJOYED THE PROGRAMS WHEN THEY SHOWED.

It is still on every week here in Nashville.

How can I copy of the book you are for her birthday ?

Look for it online where so many books are sold these days.

Laura Ingalls Wilder has been my favorite reading material as long as I can remember. There is a great history in my family of connection to the Methodist Church. My father was a Methodist minister, I am married to a Methodist minister, and also my twin sister is married to a Methodist minister. I can’t wait to read this book!

I may have failed to mention this in the book, but when Laura and Almanzo and Rose retreated to Spring Valley, Minnesota, to live with his parents, his family was a member of the Methodist church there.

I was born in the wrong millenium. I love anything Historical. I was raised in a christian family on a large dairy farm. My dad plowed with a team of horses as a teenager. I someday hope to tour the Ingalls locations, library etc. My parents did and loved it.

My dad never used horses, but we used to see the big plow horses at the Osawatomie Fair. When tractor pulls took over, it just wasn’t the same.

This is definitely on my wish list! Have loved Laura’s family since I was a girl, unfortunately not on a prairie or farm, but learned so much from her! Still do, on the old re-runs. Thank you for sharing all that you have learned! I am looking forward to reading, or listening to, this book!

You may have been fortunate not to have been on an eastern Kansas dairy farm! Dad never could get enough of a price for his milk. Stephen Hines